Hello, Tappsters!

The winning codes for the £100 Gift Vouchers were out on the app yesterday – and also sent in an email so do check those out to see if you’ve won 🎊

Right, let’s get into what we learned this week…

Show Me the Scale – Why Teachers Want Pay to Stay Fixed

If you’ve ever tried to argue for a higher salary in teaching, you’ll know it’s awkward at best, if not taboo.

Your answers this week show why: nearly four in five teachers say they’d feel uncomfortable asking for more than the offered pay. And when asked if they had ever done it? Most, especially women, said no.

Back in 2018, we published a blog under the controversial title “10% Cheaper”, after discovering women were significantly more likely to accept lower pay than men in schools. Seven years on, the story hasn’t changed.

- 72% of women say they’ve never asked for a higher wage.

- Only 28% say they’d even feel comfortable doing so.

- Men, by contrast, are nearly twice as likely to have negotiated pay in the past – and more likely to say they’d do it again.

This isn’t just a quirk of personality or culture. Social psychologists have found that women face a backlash effect when they assert themselves in pay negotiations. Speak up, and you may be labelled difficult. Stay quiet, and you get underpaid. Classic lose–lose.

Which brings us to the real hero of this week’s chart: the fixed teacher salary scale. Over 70% of teachers said they prefer pay to be determined by a national system, rather than by individual negotiation. Indeed, it was the men who agreed slightly more than women – though that’s partly because more women were undecided either way.

An argument against fixed scales is that they remove “merit” from the process. But perhaps what they really remove is women’s fear of seeming greedy. It’s worth bearing that in mind the next time someone argues for more freedoms on salaries.

Teacher Temptation: Would You Use AI?

Let’s be honest: if you were a student today, staring down an essay deadline, and ChatGPT was just sitting there…would you use it?

We put that dilemma to teachers this week, but rather than asking just one question, we asked three. Why? Because context matters. When AI use is forbidden, ambiguous, or encouraged,

your likelihood of using it changes. A lot…

Here’s what we found:

- When told not to use AI: 47% of teachers said they definitely wouldn’t use it. But 4% still said they definitely would – and 17% said it was likely. That means 1 in 5 of you would likely cheat!

- When told nothing: Just 9% stayed firmly on the “definitely not” line. 62% of you drifted into the likely/definitely category. So if you’re not being explicit with pupils, assume the majority are using it.

- When told they could use it: 80% of teachers said they likely or definitely would.

In other words, the rules make a difference – but ambiguity makes mischief!

And then there’s that gender split (again!). Women were far more likely to follow the rules. Over half said they’d never use AI if explicitly told not to – compared to just a third of men. It echoes what we saw in the pay data: women avoid risk, follow the rules, and pay the penalty for doing so. Men? More likely to push the boundary.

We already worry about a gender gap in achievement – particularly for boys in reading and writing. So what happens in a world where boys are more likely to break the rules and use AI to get ahead, while girls play it straight and fall behind?

If you’re wondering how age affects this, by the way: it mainly doesn’t. There’s almost no difference in answers between those of different ages, subjects, or regions. The only slight difference was that if you’re allowed to use AI, headteachers were the most likely to say they definitely would!

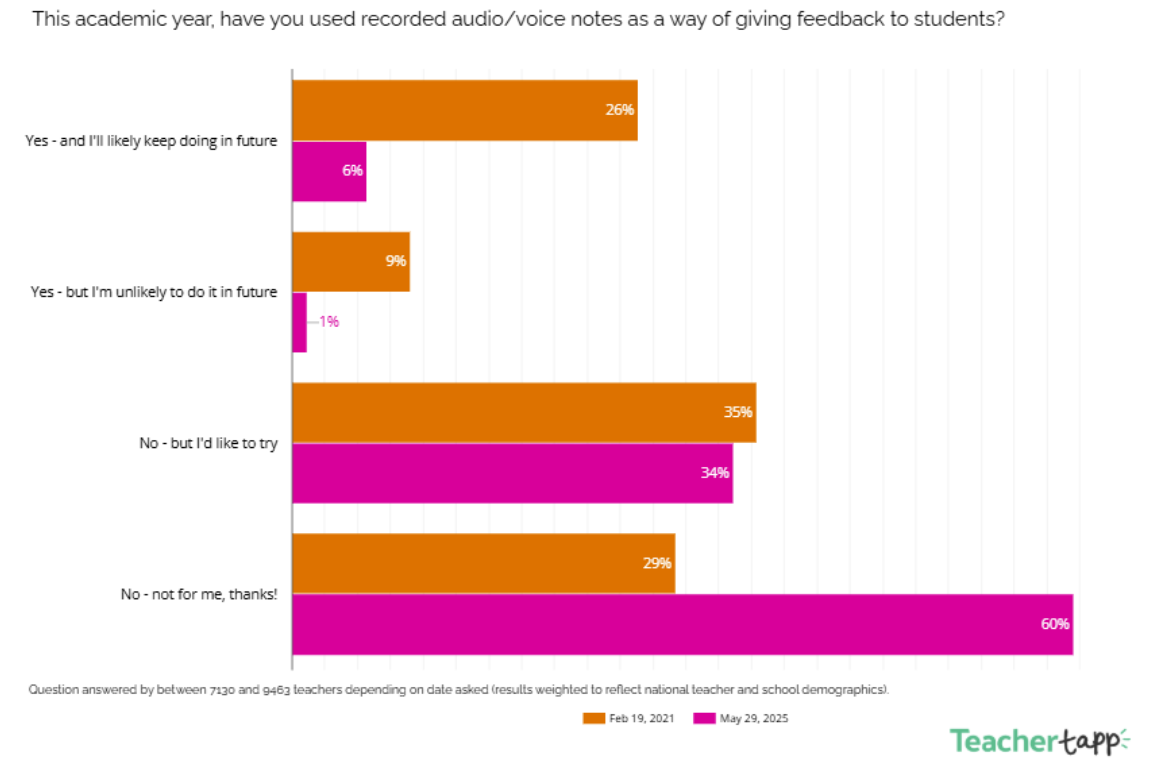

🎙️ You Said You’d Keep Voice Notes Forever…

Back in early 2021, voice notes were having a moment. Remote learning had made them popular, teachers were experimenting with all kinds of tech, and a chunk of you thought you’d solved feedback forever.

When we asked in May 2012, 35% of teachers said they hadn’t yet used voice notes for feedback – but wanted to in future. Another quarter of you – 26% were using them and planned to keep going. The optimism was real 😃

Fast forward to 2025… and it hasn’t quite panned out 😟. This year, just 6% of teachers say they’re still using voice notes for feedback. And a whopping 60% say they don’t use them – and never want to.

So what happened?

It’s another example of the intention–action gap which we talked about in last week’s blog – the psychological phenomenon where we think we’ll do something, but don’t.

Voice notes feel efficient, personal, human. But in practice? They’re fiddly. You can’t skim them. Students forget to listen. Colleagues send six-minute epics.

All of which shows that while tech can help with some things, it’s remarkable how quickly delight in a new solution fades. Ah well. Maybe AI will solve marking forever?!

🥕 The Meat-Free Menu Question

Last week a charity proposed that schools should no longer be required to serve meat at least three times per week. The story made the papers and a few Teacher Tappers got in touch to say: “Ask us what we think!”

So we did. But we didn’t just ask once.

We used it as a case study in how the framing of a question matters for policy answers, drawing on work we’ve done on question design – and a sprinkle of Daniel Kahneman’s psychology for good measure.

Step 1: The least biased version

We spent a while designing a neutral wording question. No push, no pull. Just:

“Should schools be required to serve meat at least three times per week?”

Here, 45% of teachers said no, just 32% said yes, and the rest were unsure. So, in principle, most teachers don’t want that sort of policy imposed.

Step 2: The Kahneman-style framing

Then we tried a different approach. Instead of asking about policy, we asked about personal preference:

“If your school could offer one of these menus, which would you prefer?”

Option A: Meat-focused optionsOption B: Plant-focused options

Option C: No preference

Here, the result flipped. Twice as many teachers chose the meat-heavy option over the plant-based one. So while 49% chose meat, 26% chose plants and 25% chose no preference.

So what’s going on?

First of all, these are not the same question! The first question concerns what the government requires from an organisation. I may believe the government shouldn’t dictate what schools should do ever regarding lunch. The second question is about personal preferences. In this case, a tapper can choose what they like to eat, which is likely separate from my views on government policy.

But this is exactly why psychologists like Kahneman argue that our stated values often depend on the context and hence a question framing. When asked to consider the collective, people tended to favour flexibility. But when asked what they’d personally choose on a lunchtime? Meat is most popular!

This also shows why policymaking is hard. A proposal might be popular in theory (e.g. allow schools to become vegetarian) but deeply unpopular if the trade-offs become real (ie, when staring at a no-meat menu). Cf Ofsted frameworks!

🏷️ The Curious Case of Class Names

You might be in 5B, 5 Blue, or… Jaguar Class. But one thing’s for sure: you’re almost certainly not in Miss Smith’s Class.

Only 1% of teachers say their classes are named after the teacher. Instead, modern classrooms are a riot of names borrowed from nature, geography, or the Dulux colour chart.

Here’s the breakdown:

- 41% of class names are based on colours, places, animals or other themes (hello, “Swan Class” and “Year 2 Volcanoes”).

- 35% stick with the trusty year+letter combo: Y3A, 5B, etc.

- 14% use surname initials (Class HB, for example).

- A smattering use numbers, mixed codes, or other in-house systems.

But our favourite bit? The regional differences.

The northern areas seem much more keen on simply the year group or year + letter, and much less keen on the whimsy of themes. The West Midlands seemed to be the most, well, middling. But if you’re looking for “Penguin class” then your best bet is to head to the south-east who topped the themed charts! 🐧

Daily Reads

Last week you were really keen readers! But the most-read blog was about subject development time, by Kat Howard.

Have you seen a great blog you think would make a great daily read? Let us know by emailing england@teachertapp.co.uk and we will check it out!