“If you can read this, thank a teacher”, so goes the popular saying, often found splashed across cards on ‘Thank a Teacher’ day. And what a lot of teachers we have to thank; learning to read is rightly a massive focus of primary school, and scrutinised in both national and global league tables. But is what we’re doing working for all? Figures from The National Literacy Trust reveal that only 1 in 3 children say they enjoy reading, and 25% of year 6 students do not meet the expected standard in the KS2 reading paper.

What happens after phonics?

Phonics programmes are tightly regulated in schools: there is a specific list of schemes schools can choose from, and the fidelity to the scheme is subject to scrutiny in Ofsted inspections. What happens next, however, is a different story, where the use of levelled or ‘banded’ readers (books organised by level of challenge) can differ from school to school.

A Teacher Tapper got in touch to ask us to find out how schools organise this incredibly important stage of a students’ reading journey: that moment where they move from books designed to help learn the mechanics of reading, to books that educate, excite and entertain.

We asked our primary teaching community four questions about banded readers, and more than 3,500 responded. Here is what we found out…

Use of banded readers

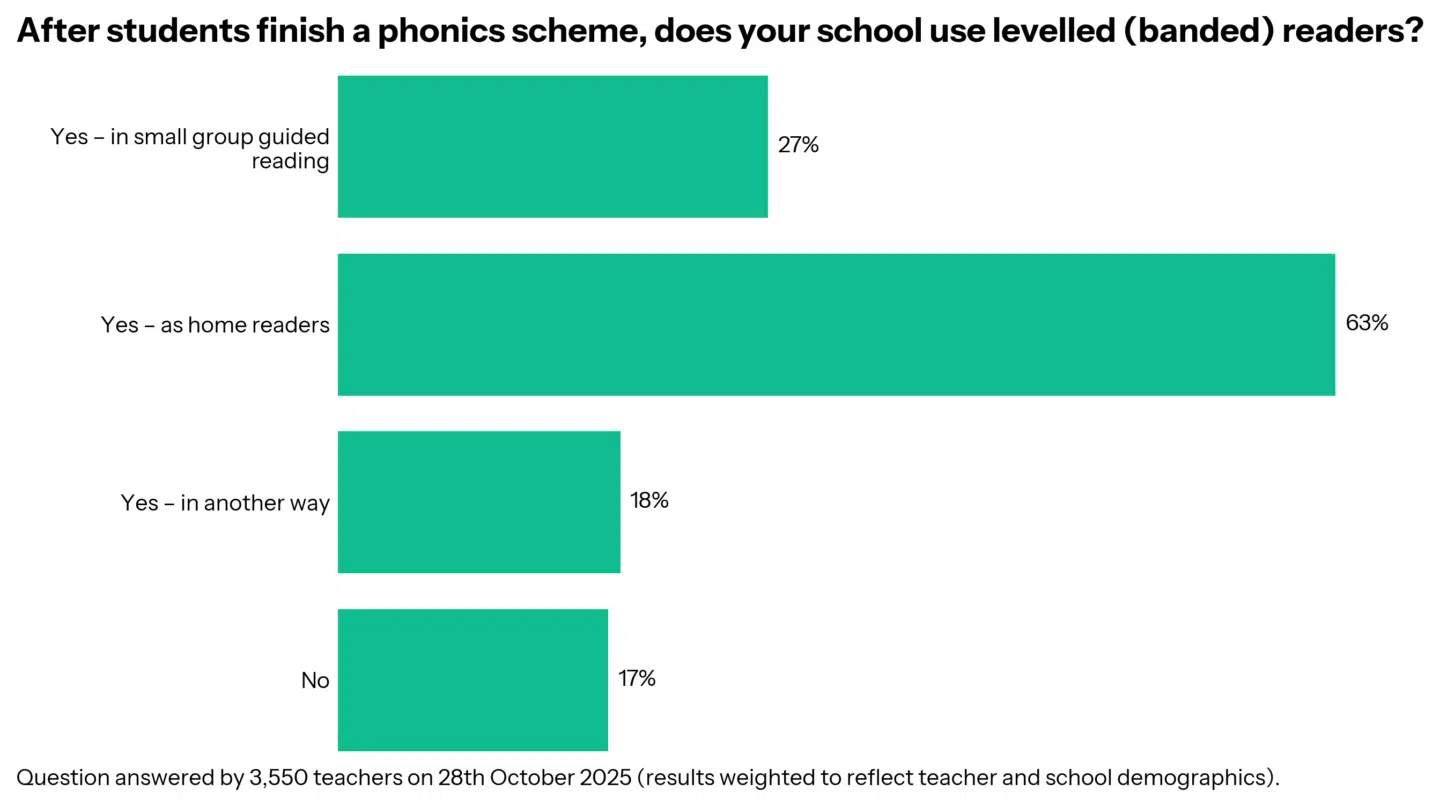

The most common way to use banded readers is as a home reader (63%), but more than a quarter use them for small group guided reading (27%), and a further 18% include them in another way in their reading plans.

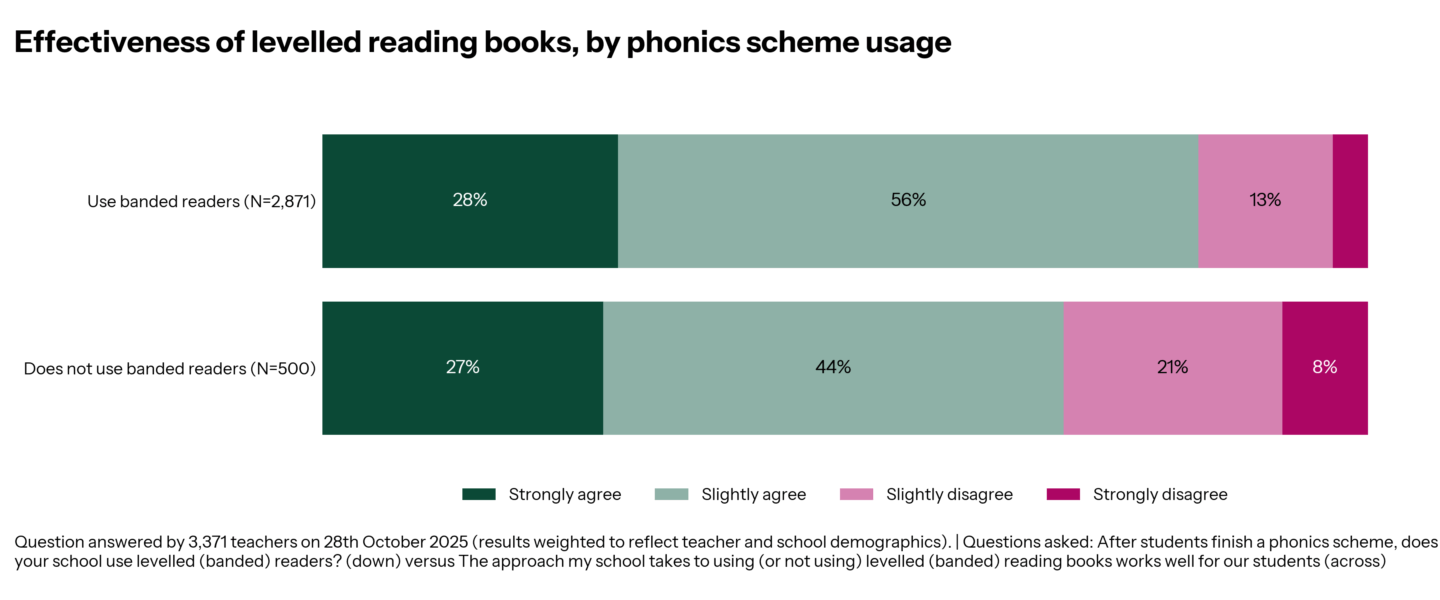

But how happy are teachers with the way their school uses these books? Teachers in schools where banded readers are used were the most likely to report that they thought the school’s use of banded readers was effective, compared to schools that did not use banded readers (84% vs 71%).

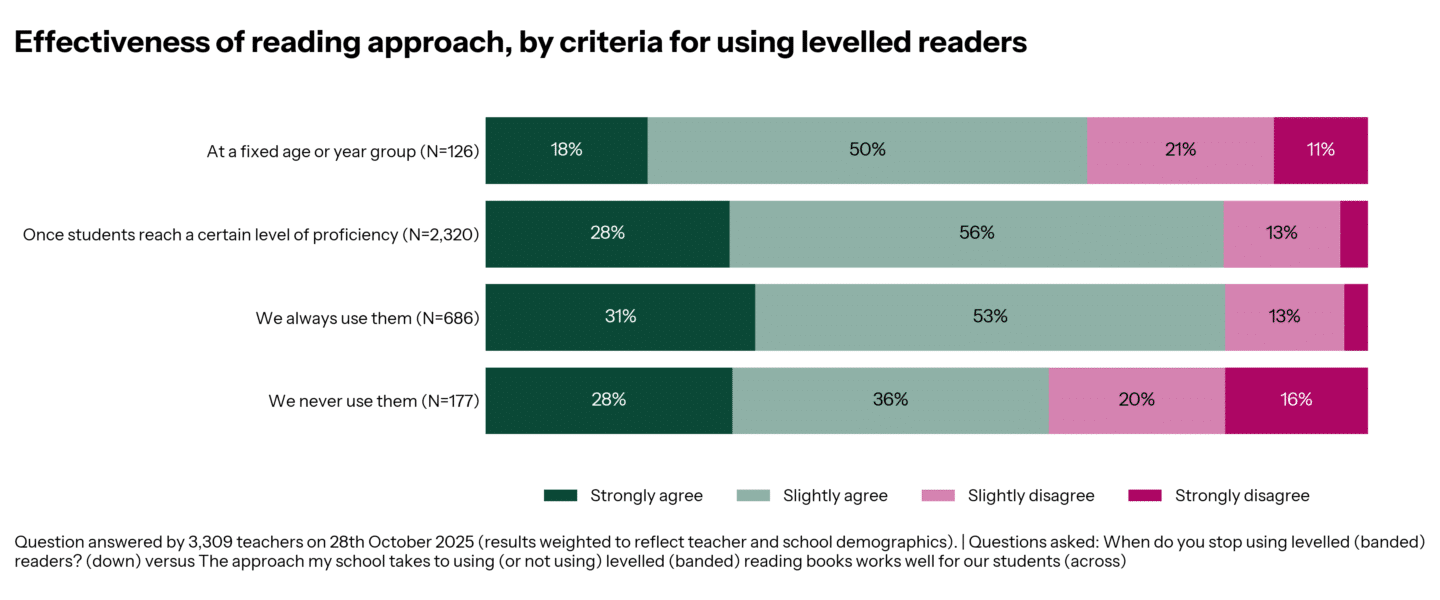

It wasn’t just how banded readers were used, but also when they stop. 73% move on from banded readers once students reach a decided level of reading proficiency, 22% continue to use them throughout KS2, and just 4% use a year group as a cut-off point.

Looking only at the two most common approaches (using them throughout primary, and stopping once students hit a level of reading proficiency), teachers report identical levels of agreement that their approach is effective (84%).

Teachers who stopped at a fixed age, or never used banded readers, were much less likely to report they think their approach was effective (68% and 64%); however, because these were much smaller groups, the confidence intervals make comparison more difficult. It might point towards reasons why some teachers are more or less likely to feel banded readers are effective in their school.

So far, so clear: schools vary in the way they approach the use of banded readers, but generally, teachers in schools where they are used are more likely to believe their approach is effective, when compared to teachers who work in schools where they do not use them – perhaps suggesting they would be happier if they were introduced. But when they’re being used, how do you do it well?

What teachers told us about banded readers

In addition to the closed-answer questions, more than 740 Teacher Tappers wrote in with their experiences. Here is what you told us about using banded readers – the good, the bad, and the tips for success!

1. Inconsistency and confusion across schools or systems

The comment that came up again and again was that the banded schemes were inconsistent. Many Tappers mentioned the fact that reading band systems differ widely between schools, publishers, or schemes 🫠. This clearly doesn’t make things easy for teachers!

- Comments highlight that there is no universal standard, so pupils moving between schools or reading schemes often experience mismatches.

- Some felt that the colour or level labels can be misleading when compared across series (e.g. Oxford Reading Tree vs Big Cat). This is super tricky if your library contains a mix of books!

“Children move schools and suddenly they’re on a different colour despite being the same level.”

“Bands mean different things in different schemes.”

2. Mismatch between bands and reading ability

The inconsistent theme continues…this time, the problem is that there is a mismatch between the bands and the reading skills. Teachers noted that reading bands often don’t accurately reflect comprehension or real reading ability.

- Children can decode text fluently but struggle with understanding or inference questions.

- Some Tappers said the band progression feels too rigid or doesn’t account for different aspects of reading (fluency, comprehension, vocabulary).

“Some children can decode but can’t understand the story at that level.”

“The bands don’t always show true reading ability.”

3. Parental pressure and misunderstanding

Not mentioned as much as the consistency issues, but still a frequently mentioned issue, was the parent problem. A recurring frustration was parental misunderstanding of what the bands mean.

- Parents often view higher bands as a sign of success, leading to pressure on teachers to move pupils up faster.

- Some mentioned that parents compare children or question teachers’ judgments.

“Parents see the bands as a competition.”

“They only want to know when their child will move up a colour.”

4. Overemphasis on Progression Rather than Enjoyment

Not so much a problem with the banded schemes, but more an issue of the concept itself: teachers expressed concern that banding systems can make reading feel transactional rather than enjoyable.

- Band progression can dominate over developing a love of reading, especially when schools track levels closely.

- Some advocated for a greater mix of banded and free-choice books.

“Children focus on moving up bands rather than enjoying stories.”

“We need to encourage reading for pleasure, not just progression.”

5. Practical Issues with Book Stock and Access

Finally, several responses shared their frustration that it wasn’t the schemes themselves that were the problem, but the struggle to properly resource it. Tappers wrote in to tell us about the shortages or imbalances in reading stock.

- Common issues included not enough books in popular bands, older or damaged sets, and difficulties keeping up with students who were ‘rapid movers’, ie moved up the bands very quickly.

“We have lots of early books but not enough in the middle levels.”

“It’s hard to keep the sets complete when books go missing.”

Mixed Feelings About Usefulness

While some teachers saw reading bands as a helpful organisational tool, others felt they are too restrictive or outdated.

- Teachers appreciate the structure for early readers, but want more flexibility for older or confident readers.

“They’re useful for the early stages but too limiting after Year 2.”

“Good for structure, but I prefer teacher judgment for moving children on.”

The good side of banded readers

Although the above can all feel quite negative, there were also positive comments. Tappers wrote in to tell us that reading bands can be an effective way to “support early reading“, offering “a clear structure for early readers” and a practical way to match books to ability.

And it wasn’t just the content of the books – many found them helpful for organisation and communication, saying they “make organising the books much easier” and give staff a shared language to discuss progress.

And although there were some who criticised banded readers for being demotivating, we also had Tappers writing in to say the opposite! Others noted that the visible steps between bands can motivate children, especially when “they feel proud when they move up a colour.”

Overall, teachers valued reading bands most when used flexibly – as “a guide rather than rigidly” – allowing space for teacher judgment and reading for pleasure alongside structured progression. Like with many tools in education, nothing is all good or all bad; it’s down to how you use it.