This September, Teacher Tapp asked teachers about accents — and how their voices are perceived by colleagues and students. We shared the results with Teacher Tapp fan and accent expert Dan Clayton to help us make sense of what the findings reveal about school life for teachers whose accents stand out.

Meet Dan Clayton

“I’m Dan Clayton and I work at the English and Media Centre in London as an education consultant,” Dan explains. “I specialise in English Language A-level and have taught for over 25 years. I’ve also worked with exam boards, academics and linguists to promote language education.”

What do we mean by “accent”?

Linguists often see accent as one part of dialect. Accent refers to how we pronounce words – the sounds of speech – while dialect includes vocabulary and grammar too. In short, accent is about sound, and dialect is about broader language patterns.

Why does accent matter for teachers?

“As teachers, our voices are our main tools,” says Dan. “We think about how to explain ideas clearly, but accent also shapes how others perceive us. It’s closely tied to identity and carries what linguists call social meaning — hints about class, region, gender, or ethnicity.”

People react strongly to accents, often based on stereotypes rather than the sounds themselves. “Those associations can affect how teachers are judged — or even how much they’re listened to,” Dan notes.

What the data shows

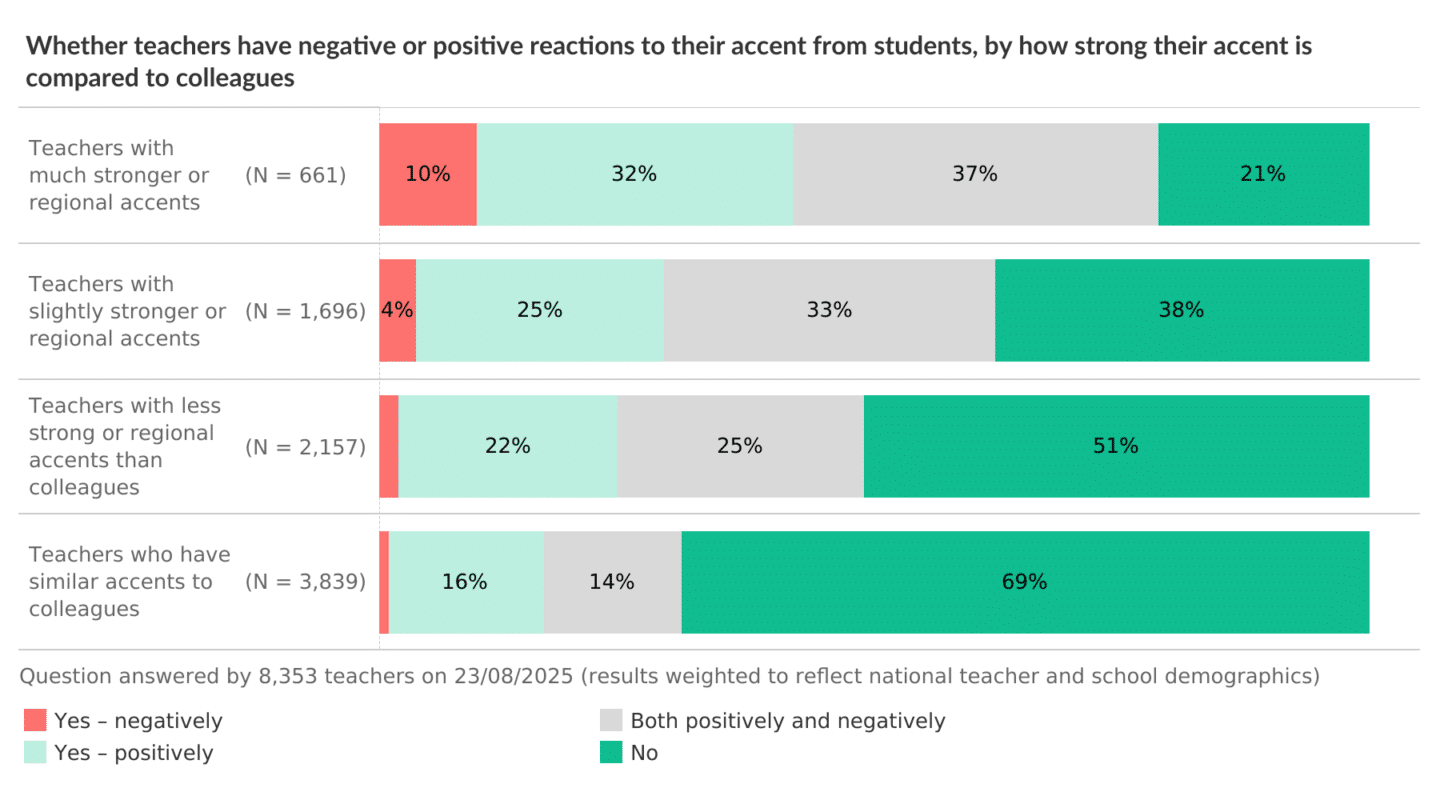

About 1,500 teachers responded to the Teacher Tapp questions.

- 26% said their accent is stronger than their colleagues’ (7% said much stronger).

- 48% said their accent is similar, and 26% said theirs is less strong.

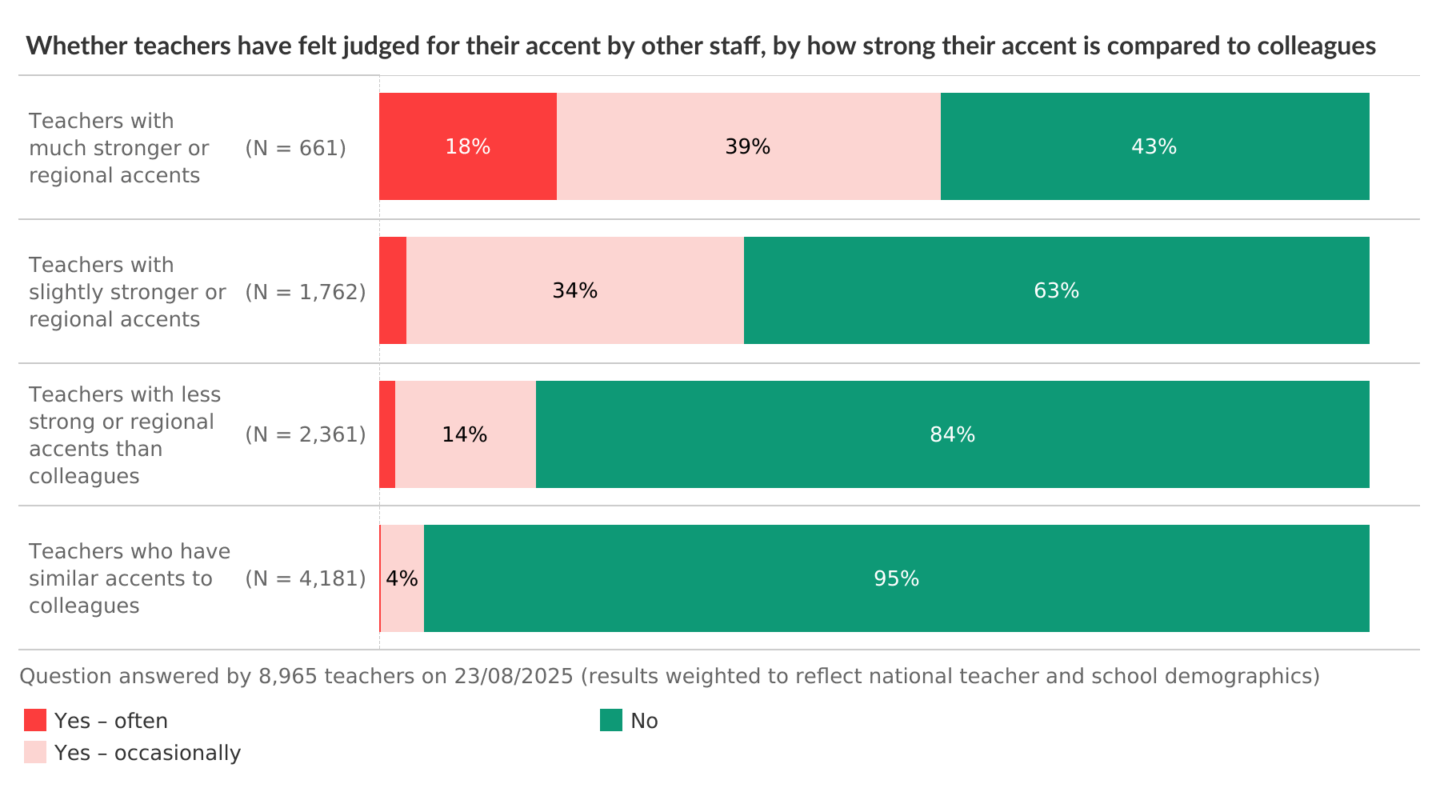

Teachers with much stronger accents than colleagues were more likely to report negative reactions from students (47% vs 17%) and colleagues (57% vs 5%).

What teachers told us

The open-text responses painted a vivid picture. Some teachers felt their accent made others assume they were less capable — one said sixth formers had questioned whether a northern-accented teacher could be “intelligent enough” to teach A-levels. Others described being mocked, especially Black and Asian teachers.

A few noted that accent could spark behaviour issues or parental complaints, often linked to prejudice. One wrote: “Teachers with certain accents are more likely to face negative behaviour from students and sometimes parents — it’s an area of racism and prejudice that isn’t being addressed.”

Yet not all experiences were negative. Some teachers saw their accent as an asset that helped build rapport with local students. “A local accent can make pupils feel seen,” said one. Others used discussions about accent as an entry point to talk about diversity and equality in class.

Still, misconceptions persisted. “I was surprised,” Dan says, “that some teachers corrected colleagues’ accents or assumed certain ones were ‘wrong’. There’s still confusion about what counts as standard English, and linguists are clear — there’s no such thing as a good or bad accent.”

Are teachers different from everyone else?

In some ways, teachers mirror the wider population — accents from across the UK and beyond. But teachers are also unique: many have studied or worked in different regions, encountering a range of accents. They’re also expected to “model good English”, a pressure that few other professions face.

“This expectation can lead to tension,” says Dan. “Teachers might feel judged for not sounding ‘standard’ enough, even though ‘standard English’ is about grammar and vocabulary, not accent.”

Studies consistently show a hierarchy of accents in the UK. Some are heard as “educated” or “trustworthy”, while others — like Brummie or Scouse — can unfairly attract negative stereotypes. Alarmingly, identical recordings judged by accent alone have even been rated as more or less criminal or threatening.

What this means for schools

“It’s a complex picture,” Dan says. “Schools should be places of learning for everyone — students and staff. That includes understanding that we all have accents and that some attract more attention or prejudice than others.”

While accent isn’t a protected characteristic, it often reflects identities that are — such as race. “Language can be a proxy for discrimination,” Dan warns. “Accent bias should be treated as seriously as any other form of bias.”

What can leaders do?

School leaders can help by treating accent-related issues as matters of fairness and inclusion, not trivia. Whole-school discussions — perhaps linked to curriculum reform in English — could encourage staff and students to explore how language and identity connect.

“Invite teachers and students into conversations about school language policies,” Dan suggests. “Help people understand what ‘standard English’ really means and why every accent deserves respect.”

Are attitudes changing?

Research from Queen Mary University of London shows that while the UK accent hierarchy still exists, the gaps are narrowing. Younger people tend to be more accepting of accent diversity, though it’s unclear whether that openness will last into later life.

“I’m hopeful,” says Dan. “There’s growing curiosity and enjoyment around accent diversity — students love to talk about it. We just need to give them the tools and understanding to do it well.”

What should we ask next?

Dan’s final thought: “We should be asking how to raise awareness. The more people understand accent bias, the less likely they are to make unfair judgements. If we can put language study at the heart of education, that’s a change worth making.”

What do you make of our findings? Write it and share your thoughts england@teachertapp.co.uk.